January is often the month of reinvention. A month for folk to assess their unpleasant habits. With many looking towards ways of revitalising themselves for the future ahead of them. Be it career, relationships or health, January is the time for people to search introspectively about their past and present choices before looking forward to a new enlightened path of self-improvement.

Todd Solondz is the kind of guy who scoffs at self-improvement.

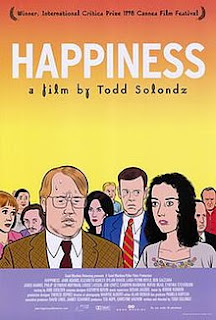

The shocking thing about Solondz’s 1998 feature Happiness is how unsettling it still is to this day. Watching the film in the era of social media only seems to highlight how much Solondz gets away with. Please note I am not mentioning too much of what happens in the film. You must see it to believe it. The film’s ironic and cynical jabs at suburbia could draw a concentrated amount of outrage. To those whom some would consider “over-sensitive.” In his four-star review of the film, Roger Ebert notes that it is “not a film for most people.” He hits the nail squarely on the head.

Solondz’s dark satire is a medley of interlocking stories involving three sisters and the immediate connections surrounding them. The film’s painful cold open is a superb litmus test for first-time viewers. The overly sensitive Joy (Jane Adams) decides to break things off with Andy (Jon Lovitz) while on a date with him to avoid complicating things. The exchange that occurs is what the younger generations would now call cringe and suggests why ghosting is now so popular among the single. If a viewer can stand to watch this conversation without wincing, then the viewer may be in good stead for the next two hours.

Happiness is uncompromising indie cinema that is tremendously comfortable when the viewer is uneasy. Revelling in hostility like a pig in shit Happiness is a grimly comic look at suburbia that landed a year before American Beauty (1999) but holds a cuttingness that lingers past the latter film’s pomposity. Solondz mines empathy out of the repulsive, finding an affinity for those who embrace the appalling. The women are shallow, while the men are pathetic. And this is before you realise that Happiness runs the gauntlet of the dark and upsetting. From obscene phone calls to full-blown paedophilia, the film challenges the viewer with the ability to dig out twigs of compassion from the unspeakable.

What makes Solondz’s movie so compelling is how it states that even the perverse may be seeking contentment. He finds the darkest humour in the absurdities and constrictions which inhabit his misanthropic characters. Rewatching Happiness was invigorating. Particularly in our current climate of self-described wellness gurus and influencers shilling false promises and dubious misinformation via their social media feeds and channels. So much time they spend dropping life lessons as if they have found the key to enlightenment. One wonders what a few of the most obnoxious types would make of a film like this. Genuine hostility? Maybe. And that is what makes Happiness funny.